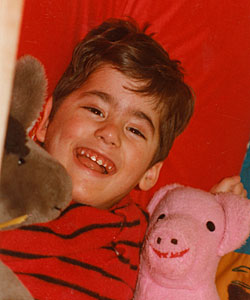

Here’s a beautiful essay I think you’ll want to share with others. It was submitted to me by Maureen Swinger, written in remembrance of her younger brother Duane. I was deeply touched and I think you will be too.

Duane was born healthy, but when he was three months old, he was attacked by his first grand mal seizure, with countless to follow. I say attacked because they were vicious, painful to witness, and never got easier to see. Diagnosed with a rare form of infantile epilepsy, he was given about a year to live. With the severe brain damage he sustained, he was never able to walk, talk, play football, hold his own in clever repartee, start a business, tour the world, fill in the blank. He was never the first or the greatest, if you measure by the yardstick of success.

Duane was born healthy, but when he was three months old, he was attacked by his first grand mal seizure, with countless to follow. I say attacked because they were vicious, painful to witness, and never got easier to see. Diagnosed with a rare form of infantile epilepsy, he was given about a year to live. With the severe brain damage he sustained, he was never able to walk, talk, play football, hold his own in clever repartee, start a business, tour the world, fill in the blank. He was never the first or the greatest, if you measure by the yardstick of success.

Nobody knows how much Duane could understand. Once some neurologists gave him an aptitude test, and when he showed no interest in differentiating a red square from a yellow triangle, the results came back: he has the cognizance of a three-month-old. We laughed. How could they possibly know how much was going on in there? If you threw a joke at him, a laugh would often bounce back to you. Other times, nothing. How to measure intelligence in someone so full of life, yet someone whose constant seizures (some too small to see) played havoc with his memory and situational awareness?

Each of us siblings had our moment to realize that it didn’t matter what he knew or didn’t know. As kids, we had prayed countless confident prayers for miraculous healing, sure that the next morning he’d be  running out of his room to meet us. But sooner or later, the thought caught up with each of us. He isn’t broken. He doesn’t need fixing. D is D, and he’s here, as he is, for a reason. If we don’t understand it, that’s our issue, not his.

running out of his room to meet us. But sooner or later, the thought caught up with each of us. He isn’t broken. He doesn’t need fixing. D is D, and he’s here, as he is, for a reason. If we don’t understand it, that’s our issue, not his.

Last November, on the day of his funeral, we again found ourselves standing shoulder to shoulder around him, in the familiar pattern we had adopted over years: D as the hub, we as the spokes. This time, though, no laughter bounced back. We looked down at his calm, still face in the simple pine casket, and marveled at the 31 years of intense and powerful living that D had crowded into his life. And the people – the hundreds of people he had collected who made the circle of his family so immeasurably wide. And the memories, and lessons learned, came flooding in. Let me tell you more.

Because Duane was my best brother, it’s hard to see him through a new acquaintance’s eyes, but if I hadn’t known him and maybe had never encountered someone with a disability, well….there he sat, his eyes often vacant, staring a hole in the ceiling. One of his wrists was noticeably contracted, and yes, he drooled. His favorite occupation seemed to be chewing on a large rag. He often didn’t respond when someone said hello, even if they loudly enunciated their greeting in his ear. He was always in a high-support wheelchair or some involved piece of therapy equipment. But talk to any of the 70-some caregivers who spent time with him over the last three decades, and none of them will mention any of this. Because that wasn’t who he was. Not even close.

Because Duane was my best brother, it’s hard to see him through a new acquaintance’s eyes, but if I hadn’t known him and maybe had never encountered someone with a disability, well….there he sat, his eyes often vacant, staring a hole in the ceiling. One of his wrists was noticeably contracted, and yes, he drooled. His favorite occupation seemed to be chewing on a large rag. He often didn’t respond when someone said hello, even if they loudly enunciated their greeting in his ear. He was always in a high-support wheelchair or some involved piece of therapy equipment. But talk to any of the 70-some caregivers who spent time with him over the last three decades, and none of them will mention any of this. Because that wasn’t who he was. Not even close.

D didn’t get the chance to pick his friends at all. People flowed into his life in an uninterrupted stream, and he took all comers. No matter how messed up or how great you thought you were, you started out on a basis of trust, and a “let’s see where we go from here” attitude.

Since Duane didn’t judge people, we did it for him. Our family was very close. All five of us kids were born within a year of the next, with D right in the middle. We were fiercely proud of him, and if we felt anyone was staring at him, ignoring him, or talking down to him, our hackles rose. But over time it became obvious that we were too quick on the draw. We should have understood that if given time, D would always introduce himself on his own terms.

Introductions did take time – the sort where the clock slows waaay down and communication signals can’t be cracked without a code. But once you knew Duane and he knew you (the latter usually happened first), you had a friend for life. And it was the kind of friend people wish for and never get: mercilessly honest and completely steadfast.

When Duane was mad, the world knew it. If he was done sitting around (church, dinner, graduation, whatever) he let you know with a big “get me out of here” roar that continued till he was acknowledged and whisked out. He didn’t really consider our emotions on this one, and whoever was sitting next to him would be hunched over, toes curled in embarrassment. You’d want to shout, “D, is it that bad? Everyone’s looking at us!” Once a situation was defused, however, he forgot it. A glass of water, a chance to stretch out some sore muscles, and he was fine. Life was good.

There was a lot of potential for hurt in Duane’s basic living routine. You had to watch not to park him an inch too close to the table. His brakes had to be set, his seat belt always buckled, his transfers from bed to chair done with great gentleness and strength. His eight different medications had to be administered in the right combination at just the right time. Through it all, D was enormously patient about everything. Mom called him noble, and that says it best. Yes, he could holler when he had to, but I have never encountered such grace under fire anywhere else. His forgiveness turned on a dime. You knew that he loved you and trusted you through all the bumps and lurches and things that did not go right.

There was a lot of potential for hurt in Duane’s basic living routine. You had to watch not to park him an inch too close to the table. His brakes had to be set, his seat belt always buckled, his transfers from bed to chair done with great gentleness and strength. His eight different medications had to be administered in the right combination at just the right time. Through it all, D was enormously patient about everything. Mom called him noble, and that says it best. Yes, he could holler when he had to, but I have never encountered such grace under fire anywhere else. His forgiveness turned on a dime. You knew that he loved you and trusted you through all the bumps and lurches and things that did not go right.

There were a handful of guys from the National Guard – friends of a friend – at Duane’s funeral. Maybe that’s what got me thinking of D’s life as something militant, in the most peaceful way imaginable. There they stood, tall and erect, shoveling earth into his grave with such respect and dignity – for someone who never could stand, let alone straight. (What does he look like now, wherever he is? I have this image of him throwing his shoulders back, standing to his full six feet, and then, free of that blasted wheelchair, breaking into a joyous sprint.)

Yes, D was a warrior. Not the kind that kills to protect, but the kind that shields others who don’t even know they need protection. He’s not the only one: there are others deployed around us. Their placement in our lives is not an accident. Anyone the world calls weak, helpless, useless…that’s our clue. We’d better take a closer look, because they know something we don’t know.

Yes, D was a warrior. Not the kind that kills to protect, but the kind that shields others who don’t even know they need protection. He’s not the only one: there are others deployed around us. Their placement in our lives is not an accident. Anyone the world calls weak, helpless, useless…that’s our clue. We’d better take a closer look, because they know something we don’t know.

At Duane’s graveside, surrounded by over three hundred of his friends, our family was standing amid the flowers and candles under a rare November sun, when another warrior marched up and confidently took his place between my parents. Born with Noonan Syndrome and severely disabled, Alan has been carrying his torch high for fifteen years, so you couldn’t pull out any trite phrases about torches being passed to new generations. But I could almost hear D saying, as a soldier transferred to a higher unit might say to a younger comrade, “Go get ’em, tiger. Crack some more hearts open.”

Author’s bio: Maureen Swinger is a writer and mother of 2 young children. She and her husband Jason live in Lakeville, Connecticut.

Back to Top